___________________________________________________________

(The "Al Chet" confession of sins is said ten times in

the course of the Yom Kippur services: Following the Amidah of the afternoon

prayers of the day before Yom Kippur; just before sunset on Yom Kippur Eve; and

twice during each of the following services--the evening service of yom Kippur

eve, and the morning service, the Musaf service and the afternoon service of

Yom Kippur day--once at the end of the Silent Amidah, and once during the

cantor's repitition of the Amidah.)

Extracts from:

“EXPLORING

THE AL-CHET PRAYER”

by Rabbi Shraga Simmons

When one begins to look at the task of teshuva (repentance), it

can be overwhelming. We've made so many mistakes this past year that it's hard

to know where to begin! Clearly, if we don't have an excellent system for

tackling this project, it will be very time consuming and draining.

In Judaism we say that if you can get to the root of the problem,

you can eliminate it entirely. That is the goal of the "Al Chet"

prayer that we say so many times during Yom Kippur services. The 44 statements

comprising "Al Chet" are not a list of mistakes, but rather identify

the roots of mistakes.

We'll examine the "Al Chet" prayer, one statement at a

time. But remember: "Change" is a process that doesn't happen

immediately. Don't try to conquer too many things at once; it may be too

overwhelming. Instead, choose the areas that cut closest to the root of your

problems. This will maximize your success in the Teshuva process.

1. For the mistakes we committed before You under duress and

willingly.

How can we be held accountable for mistakes committed under

duress?! The answer is that sometimes, we get into compromising situations

because we are not careful. Many of these "accidents" can be avoided

by setting limitations to avoid temptation.

Ask yourself:

Duress:

Did I put myself into compromising situations, and then when I got

into trouble rationalize by saying it was "unavoidable" or

"accidental?"

Have I tried making "fences" so that I won't transgress?

Have I considered setting up a penalty system as a deterrent

against certain mistakes?

When I legitimately got into an unavoidable situation, did I stop

to consider why God might want me to experience this particular challenge?

Willingly:

Did I make mistakes because I was lazy, or because my lower,

animalistic urges were getting the better of me?

2. For the mistakes we committed before You through having a hard

heart.

Hardening of the heart means that I closed myself off to deep,

human emotions like compassion and caring. The newspapers and streets seem so

filled with one tragic story after another, that I can become desensitized to

the whole idea of human suffering.

Ask yourself:

Did I ignore the poor and the weak?

When I did give charity, was it done enthusiastically or

begrudgingly?

Was I kind, compassionate and loving when my family and friends

needed me to be?

Do I feel the pain of Jews who are assimilating, and of how that

impacts the Jewish nation as a whole?

3. For the mistakes we committed before You without thinking (or

without knowledge).

Every day, a Jew prays to God for the ability to think and reason.

A clear mind is integral to our growth and development. If we're riding in a

car and staring aimlessly out the window, then for those precious moments we

are nothing more than zombies.

Ask yourself:

Do I carefully examine my society and surroundings, weighing out

what is right and what is wrong?

Do I constantly review my major goals in life?

Do I strive for a constant awareness of the presence of God?

Is one of my goals in life to be a "thinking"

individual?

4. For the mistakes we committed before You through things we

blurted out with our lips.

A wise man once said, "You don't have to say everything you

think." The Talmud says that when we speak, our lips and teeth should act

as "gates," controlling whatever flows out.

Ask yourself:

Do I think before I speak?

Am I prone to thoughtless outbursts?

Do I make hasty promises that I am unlikely to fulfill?

5. For the mistake we committed before You in public and in

private.

Ask yourself:

Public:

Did I do foolish or degrading things to attract attention or

approval?

On the other hand, did I do good deeds in public, that I otherwise

wouldn't have done -- simply so that others would see me?

Private:

Did I act privately in a way that I would be ashamed if anyone

found out?

Did I consider how God is watching even in my most private

moments?

Did I convince myself that because nobody sees me, the mistakes

somehow don't count?

6. For the mistakes we committed before You through immorality.

When the Torah speaks of immorality, it usually refers to sexual

immorality. Since sex is the strongest human drive (next to survival itself),

it can therefore be used to achieve the greatest degree of holiness, or -- as

we so often witness -- the greatest degree of debasement.

Ask yourself:

Did I speak or act in a way that lowered sexuality as a vehicle

for spiritual connection?

Do I realize how sexual immorality reduces the spiritual potential

of future, more holy unions?

7. For the mistakes we committed before You through harsh speech.

Speech is the unique human faculty, and is the way we build

bridges between each other -- and through prayer, with God. That's why abuse of

speech is considered one of the gravest mistakes possible.

Ask yourself:

Did I speak to anyone in a harsh and forceful manner?

Did I gossip?

Did I engage in idle chatter that wasted my time and that of

others?

Did I seek opportunities to elevate others with an encouraging

word?

8. For the mistakes we committed before You with knowledge and

deceit.

As we know, knowledge is a powerful tool -- and a dangerous weapon

when misused.

Ask yourself:

Did I use knowledge of a certain situation to deceive others?

Did I use knowledge to deceive myself -- i.e. did I rationalize

away my bad actions?

Did I use knowledge to circumvent the spirit of the law?

Did I use knowledge to show off and impress others?

9. For the mistakes we committed before You through inner

thoughts.

The Talmud says that "Bad thoughts are (in one way) even

worse than bad deeds." This is because from a spiritual perspective,

"thoughts" represent a higher dimension of human activity.

("Thoughts" are rooted in the spiritual world; "deeds" are

rooted in the physical world.)

Ask yourself:

Did I think in a negative way about people, or wish bad upon them?

Did I fantasize about doing bad deeds?

10. For the mistakes we committed before You through wronging a

friend.

"Friendship" is one of the highest forms of human

activity. When we reach out and connect with others, we experience the unity of

God's universe, and bring the world closer to perfection.

Ask yourself:

Did I strive to go out of my way to help friends, based on my

commitment to be their friend?

Was I insensitive toward my friends' needs, or did I hurt their

feelings?

Did I take advantage of someone who trusted me as a friend?

Have I made a conscious effort to learn how to be a better friend?

11. For the mistakes we committed before You through insincere

confession.

On Yom Kippur when we say each line of the "Al Chet"

prayer, we gently strike our heart -- as if to say that it was "passion

and desire" that led to these mistakes. Do we really mean it?

Ask yourself:

Did I ever apologize without being sincere?

Have I committed myself to "change" without seriously

following up?

12. For the mistakes we committed before You while gathering to do

negative things.

Engaging in evil as a lone individual is bad enough. But just as

the secular courts treat "conspiracy" more seriously, so too God

despises the institutionalizing of bad habits.

Ask yourself:

Am I part of a regular group that discusses negative things?

Did I participate in a gathering that led to negative activities?

Am I careful to associate only with moral and ethical people?

13. For the mistakes we committed before You willfully and

unintentionally.

Willfully:

Did I ever "act out" in a desire to demonstrate my

independence from God?

Unintentionally:

Did I make mistakes out of carelessness? Could they have been

avoided?

14. For the mistakes we committed before You by degrading parents

and teachers.

Parents and teachers are our first authority figures in life, and

by way of association they teach us how to be respectful toward God and His

mitzvot. The breakdown of respect for parents and teachers corrodes the moral

core of society.

Ask yourself:

Parents:

Do I sometimes think poorly of my parents?

Do I ever actually communicate a dislike toward them?

Do I make the effort to appreciate how much my parents have done

for me?

If I were a parent, what would I want from my children? Am I

giving that now to my parents?

Do I give special attention to the needs of the elderly?

Teachers:

Have I maximized opportunities to learn from rabbis and teachers?

Have I actively sought the guidance and counsel of wise people?

15. For the mistakes we committed before You by exercising power.

God apportions to everyone exactly what they need: whether wealth,

intelligence, good fortune, etc. Only when we feel our position is independent

of God do we seek to dominate others for our own advantage.

Ask yourself:

Did I take advantage of those who are weak -- either physically,

economically or politically?

Did I manipulate or intimidate someone into doing something he'd

really rather not have?

16. For the mistakes we committed before You through desecrating

God's name.

As a "Light Unto the Nations," every Jew is a messenger

of God in this world, responsible to project a positive image.

Ask yourself:

Did I ever act in a way that brought less honor and respect to

God?

Did I ever act in way that gave a bad impression about what it

means to be a Jew?

Did I take every opportunity to enlighten others about the beauty

of Torah?

17. For the mistakes we committed before You with foolish speech.

People have a habit of talking for talking's sake. When we're

bored, we may get on the phone, and "talk and talk and talk." Don't

talk without a purpose. In any conversation ask yourself: "Is there any

point to this conversation? Am I learning anything? Am I growing?" If you

can't identify the point, there probably is none.

Ask yourself:

Did I waste time by talking about trivial things?

Do I seek to share words of Torah at every opportunity?

18. For the mistakes we committed before You with vulgar speech.

Did you ever find yourself in the middle of a distasteful joke? It

can be insidious, but all of a sudden you find yourself dragged into a

discussion that has taken a turn for the worse. Learn to switch tracks. Monitor

your conversations, and when you notice them slipping off track, pull them

back, gently and subtly.

Ask yourself:

Did I contaminate my mouth with vulgar speech?

Did I listen to vulgar speech or jokes?

Did I protest when I heard vulgar speech?

Do I always express myself in the most pleasant way possible?

19. For the mistakes we committed before You with the Yetzer Hara

(evil inclination).

The Yetzer Hara is that little voice inside each of us that tries

to convince us to pursue physical comfort, at the expense of greater spiritual

pleasures.

Ask yourself:

Have I pursued my physical drives for their own sake -- without

involving any spiritual dimension?

Do I resort to the excuse that "I couldn't help myself"?

Have I studied Torah techniques for channeling physical drives

into holiness?

20. For the mistakes we committed before You against those who

know, and those that do not know.

Ask yourself:

Have I wronged people behind their backs?

Have I wronged people to their faces?

21. For the mistakes we committed before You through bribery.

Bribery is most subversive because we are often not aware of how

it affects our decisions. In the words of the Torah, bribery is

"blinding."

Ask yourself:

Have I compromised my honesty and integrity because of money?

Have I compromised myself for the sake of honor and flattery?

Have I failed to do the right thing because I wanted approval?

22. For the mistakes we committed before You through denial and

false promises.

The mark of a great person is a meticulous commitment to truth --

despite whatever hardships, embarrassment, or financial loss might be involved.

Ask yourself:

Have I lied to myself?

Have I lied to others?

Does my job ever involve having to lie?

Have I rationalized the acceptability of a "white lie?"

23. For the mistakes we committed before You through negative

speech (Loshon Hara).

It is said that big people talk about ideas, medium people talk

about places and things, and little people talk about people. Gossip causes

quarrel and division amongst people -- and tears apart relationships, families,

and even entire communities. As King Solomon said: "Life and death are in

the hands of the tongue" (Proverbs 18:21).

Ask yourself:

Do I enjoy gossip?

When I hear gossip, do I accept it as true, or do I reserve

judgment?

Have I set aside time to study Jewish law on how to avoid Loshon

Hara?

24. For the mistakes we committed before You through being

scornful (or scoffing).

Ask yourself:

Did I mock and ridicule serious things?

Did I make fun of someone who I considered less intelligent or

attractive?

Did I shrug off constructive criticism as meaningless?

25. For the mistakes we committed before You in business.

Integrity is the mark of every great person. The Talmud says that

the first question a person is asked upon arriving in heaven is: "Did you

deal honestly in business?"

Ask yourself:

Have I been scrupulously honest in all my financial transactions?

Was I harsh in trying to beat the competition, or did I seek ways

for us both to thrive?

Have I chosen a career that gives me freedom to pursue my personal

and spiritual goals as well?

When I was successful in business, did I show my appreciation to

God for that success?

26. For the mistakes we committed before You with food and drink.

Eating is such an essential human activity, that the rabbis say

all of a person's character traits are revealed at the dinner table.

Ask yourself:

Did I eat in order to gain energy to do mitzvot, or did I eat for

the sake of the animalistic act alone?

What secondary activity did I do while eating? Did I read the

paper and watch TV? Or did I engage in meaningful conversation?

Have I made every effort to eat kosher food?

Did I express gratitude to God for providing me with the food?

Did I overeat?

Did I eat unhealthy foods?

Did I waste food?

27. For the mistakes we committed before You through interest and

extortion.

Gaining financial advantage because someone else is destitute

shows poor character. That is why the Torah forbids loaning money to another

Jew on interest.

Ask yourself:

Have I made a profit as a result of someone else's misfortune or

downfall?

Am I greedy?

Am I stingy?

Do I feel responsible for helping to satisfy the needs of others?

Do I appreciate the Torah prohibition against charging interest --

and have I studied these laws?

28. For the mistakes we committed before You by being arrogant.

The trait the Torah uses to describe Moses is "the most

humble man." Humility is a key to spiritual growth, because it allows us

to make room in our life for other people - and for God.

Ask yourself:

Have I made others feel lowly in order to raise myself higher?

Do I dress and speak in a way that draws extra attention to

myself?

When walking through a door, do I usually go first, or let others

go first?

29. For the mistakes we committed before You with eye movements.

Sometimes we can harm others without even saying a word. For

instance, the Talmud discusses the illegality of staring into someone else's

home or yard.

Ask yourself:

Did I look at someone else's private things that were not my

business?

Did I gawk at an accident scene on the freeway?

Did I look at the opposite gender in an inappropriate and

disrespectful way?

Did I signal my disdain for another person by rolling my eyes?

30. For the mistakes we committed before You with endless

babbling.

Often we feel uncomfortable with silence, so we fill the time with

meaningless chatter. The Torah tells us, however, that more than anywhere, God

is found in the sound of silence.

Ask yourself:

Do I participate in conversations with no meaningful content?

Do I think before speaking and measure my words carefully?

Am I careful to concentrate when reciting prayers and blessings?

31. For the mistakes we committed before You with haughty eyes.

The Talmud says that a person's eyes are the "window to the

soul." An arrogant person is therefore referred to as having "haughty

eyes."

Ask yourself:

Do I communicate warmth and care to people with my eyes?

Have I avoided interacting with certain people because I felt they

were too unimportant for me?

Have my career and relationships suffered because my ego is

over-inflated?

32. For the mistakes we committed before You with a strong

forehead (brazenness).

The Talmud says there are three traits which characterize Jews:

kindness, compassion, and shame. "Shameful" means feeling embarrassed

and remorseful when doing something wrong.

Ask yourself:

Do I examine the moral consequences before making difficult

decisions?

Do I appreciate how my moral behavior defines me as a human being?

Have I studied what Judaism says about conscience and morality?

33. For the mistakes we committed before You in throwing off the

yoke (i.e. refusing to accept responsibility).

Judaism defines greatness as having a greater degree of responsibility.

Deep down this is what every human being wants -- hence the excitement over a

promotion or raising a family.

Ask yourself:

Have I accepted family responsibilities, and gladly assisted

whenever needed?

Do I keep my commitments to friends?

Do I show up on time?

Would my colleagues describe me as "reliable and

dependable?"

Have I taken responsibility for the problems in my community?

Have I accepted my unique responsibilities in this world as a Jew?

34. For the mistakes we committed before You in judgment.

The Torah tells us it is a mitzvah to be dan li-kaf zechus

-- to judge people favorably. This means, for example, that when someone shows

up an hour late, rather than assume they were irresponsible, I should rather

try to get all the facts, and in the meantime, imagine that perhaps they were

delayed by uncontrollable circumstances.

Ask yourself:

Am I in the habit of judging people favorably?

Do I wait to make any determination until I have all the

information?

Do I sometimes judge God unfairly?

35. For the mistakes we committed before You in entrapping a

friend.

Ask yourself:

Have I violated the trust of people who have confidence in me?

Have I divulged confidential information?

Have I taken advantage of family and friends by manipulating them

into doing me favors?

36. For the mistakes we committed before You through jealousy

(lit: "a begrudging eye").

Someone who has a "good eye" will sincerely celebrate

the success of others, while someone with an "evil eye" will begrudge

the success of others.

Ask yourself:

Do I experience resentment at the success of others? Or do I

experience genuine joy?

Do I feel that others are undeserving of their success?

Do I secretly wish to have my neighbor's things for myself?

37. For the mistakes we committed before You through

light-headedness.

Sometimes we can forget that life is serious. We're born, and we

die. What have we made of our lives? Have we been focused on meaningful goals,

or are we steeped in trivial pursuits?

Ask yourself:

Do I spend time reading unimportant sections of the newspaper, or

listening to frivolity on the radio?

Do I spend time with friends and colleagues discussing

inconsequential details of sports and entertainment?

Do I act with proper reverence when I'm in a synagogue or learning

Torah?

Do I speak about Biblical personalities and our Jewish Sages with

the proper respect?

38. For the mistakes we committed before You by being

stiff-necked.

In the Torah, God refers to the Jewish people as

"stiff-necked." This is a positive attribute in the sense that we are

not easily swayed by fad and fashion. Yet on the negative side, we can also be

unreasonably stubborn.

Ask yourself:

When I'm involved in a disagreement, am I frequently anxious and

upset, rather than calm and rational?

Do I think that I'm always right? Do I usually let the other

person speak first, or do I always want to speak first?

Do I listen attentively to the other side?

Have I been single-minded and lost my objectivity just because I

really wanted something?

39. For the mistakes we committed before You by running to do

evil.

Ask yourself:

When I transgressed the Torah, did I do so eagerly?

Did I run to do mitzvot with the same enthusiasm?

Did I slow down when reciting blessings and prayers?

After completing a certain obligation, do I run out as fast as

possible?

40. For the mistakes we committed before You by telling people

what others said about them.

Ask yourself:

Have I encouraged contention, and turned people against each

other?

Did I reveal secrets?

Have I studied the Jewish laws prohibiting such speech?

41. For the mistakes we committed before You through vain oath

taking.

One of the Ten Commandments is "not to take God's Name in

vain." Integral to our relationship with God is the degree to which we show

Him proper respect.

Ask yourself:

Have I been careful not to utter God's Name casually? (Or worse

yet: "I swear to G--!")

When I use God's Name in a blessing or prayer, do I concentrate on

the deeper meaning of His Name?

Have I sworn or promised falsely while invoking God's Name?

42. For the mistakes we committed before You through baseless

hatred.

The Talmud tells us that more than any other factor, hatred among

Jews has been the cause of our long and bitter exile. Conversely, Jewish unity

and true love between us is what will hasten our redemption.

Ask yourself:

Was I disrespectful toward Jews who are not exactly like me in

practice or philosophy?

When I disagree with someone on an issue, have I let it degrade

into a dislike for the person himself?

When I saw a fellow Jew do evil, did I hate only the deed, or did

it extend into a hatred for the person himself?

When someone wronged me, was I eager to take revenge?

When someone wronged me, did I bear a grudge?

43. For the mistakes we committed before You in extending the

hand.

Ask yourself:

Have I withheld from touching things that don't belong to me?

Have I stretched forth my hand to the poor and the needy?

Have I joined hands with wicked people?

Have I extended my hand to help in community projects?

44. For the mistakes we committed before You through confusion of

the heart.

The Sages tell us that ultimately all mistakes stem from a

confusion of the heart. This is why on Yom Kippur we tap our chest as we go

through this list of "Al Chet's."

Ask yourself:

Have I not worked out issues because of laziness?

Have I made mistakes because I emotionally did not want to accept

what I logically knew to be correct?

Have I properly developed my priorities and life goals?

Am I continually focused on them?

_http://www.aish.com/hhYomK/hhYomKDefault/Exploring_the_Al-Chet_Prayer.asp

______________________________________________________________

The Servant of Jehovah:

The Sufferings of the Messiah

and the Glory That Should Follow

by

David Baron

(1922)

The following remarkable hymn, by the famous

hymn-writer, Eleazar ben Qualir, (A Jew living in

Italy, who wrote liturgical Hebrew songs for synagogue services – commentary by

compiling editor) who, according to the Jewish historian, Zunz, lived in

the ninth century A.D., is taken from the Service for the Day of Atonement.9

|

9.

Cf. The Festival Prayers, with David Levi's English translation, vol. iii. p.

33. The translation has been revised by me.

|

In it are gathered up

the teachings of the Synagogue about a suffering Messiah.

"Before the

world was yet created,

His dwelling-place and Yinnon10

|

10.

"Yinnon" is, according to Babylonian

Sanhedrin 98b, one of Messiah's names according to Psalm 72:17, which the Talmud

renders, "Before the Sun, Yinnon (Heb., shall flourish) was His

name," the name indicating the pre-existence of the Messiah.

|

God prepared.

The Mount of His house, lofty from the beginning,

He established, ere people and language existed.

It was His pleasure that there His Shekhina should dwell,

To guide those gone astray into the path of rectitude.

Though their sins were red like scarlet,

They were preceded by 'Wash you, make you clean.'

If His anger was kindled against His people,

Yet the Holy One poured not out all His wrath.

We are ever threatened by destruction because of our evil deeds,

And God does not draw nigh us—He, our only refuge.

Our righteous Messiah has departed from us,

We are horror-stricken, and have none to justify us.

Our iniquities and the yoke of our transgressions

He carries who is wounded because of our transgressions.

He bears on His shoulder the burden of our sins,

To find pardon for all our iniquities.

By His stripes we shall be healed—

O Eternal One, it is time that thou shouldst create Him anew!

O bring Him up from the terrestrial sphere,

Raise Him up from the land of Seir,11

|

11.

Seir stands here for Edom, and by Edom the Talmud means Rome, where, as we

have seen above, the Messiah already lives in deep humiliation and suffering.

|

To announce salvation

to us from Mount Lebanon,12

|

12.

Lebanon stands here for the Mount of the Temple, from which Messiah is to

proclaim to Israel that the time of salvation has come.

|

Once again through

the hand of Yinnon."

http://juchre.org/isaiah53/contents.htm

______________________________________________________________

Extracts from:

“JUDGMENT

TEMPERED WITH MERCY”

by Rabbi Noson Weisz

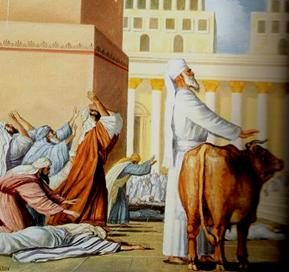

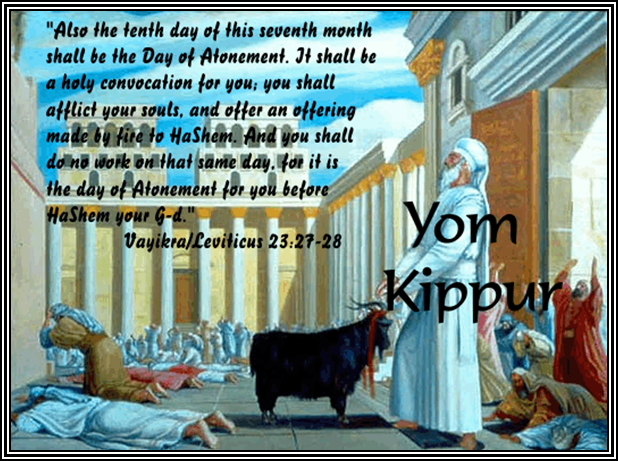

For on this day he shall provide atonement for you to cleanse you;

from all your sins before the Lord shall you be cleansed. (Leviticus 16:30)

A day of atonement and cleansing does not feel like a day of

judgment. Yet we know that the final seal on a person's fate for the following

year is stamped on Yom Kippur. It is the final day of the Days of Awe, which

are all days of judgment. In what way does Yom Kippur differ from the rest?

What is the meaning of this day of judgment, on which decisions regarding life

and death are finalized, and which is considered a day of spiritual cleansing?

Nachmanides (Vayikra, 23,24) explains that the difference between

Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur is that Rosh Hashana is a day of judgment that is

tempered with mercy, whereas Yom Kippur is a day of mercy that is tempered with

judgment. We shall attempt in this essay to plumb the deeper meaning of these

words.

Let us begin our search for the quality of this day with the

Talmud.

Rabbi Ami taught: "The numerical value of the word haSatan,

meaning 'the Satan' in Hebrew is 364 (heh=5, shin=300, tet=9,

nun=50, for a total of 364)." Explains the Ran: "The days of

the solar year are 365; there is one day where the Satan has no permission to

do his thing; that day is Yom Kippur" (Nedarim, 32a).

Does this mean that man has no free will on Yom Kippur? Obviously

not! The Torah itself outlines the consequences of failing to observe the fast

of Yom Kippur or the prohibition against work; obviously people have the free

will to do as they wish on Yom Kippur as on any other day. What significance

does the Satan's day off have for us? And for that matter who is the Satan?

Who is Satan?

Reish Lakish taught: "Satan, the Evil Inclination, and the

Angel of Death are all one and the same" (Baba Basra, 16a).

Thus the negative force is subdivided into three parts:

- It urges people to commit sins, (evil

inclination);

- It then prosecutes them for performing

these sins in the heavenly court, (the Satan);

- And finally carries out the sentence of

death issued by the heavenly court as retribution for the commission of

sins.

These negative phenomena are all elements that exist in the world

as it is today. In the World to Come, there is no death. Just as there is no

death, there is no Evil Inclination, and there is no sin and nothing to

prosecute. Thus the entire personality of the Satan is one that exists only in

our world. We all hope to experience the sphere of existence where the Satan

will not be present at all.

This world has wars and tribulations. The Evil Inclination, the

Satan, and the Angel of Death has power to rule in this world, but the World to

Come has no tribulation or sighs or subjugation; it has no Evil Inclination, no

Satan and no Angel of Death as it is written, "He will eliminate death

forever and my Lord God will erase tears from all faces" (Isaiah, 25:8)

(Ozer Midrashim, 146).

If the Satan has a day off on Yom Kippur, this means that Yom

Kippur is really a day that belongs to the World to Come rather than this

world. Indeed the Yom Kippur service attests to this in many ways. The one that

is most germane to our topic is the following: The Kohen Gadol, the High

Priest, called out the forbidden God's name in public 10 times on Yom Kippur.

The significance of this is clear from the following passage of the Talmud.

"And God will become King over all the earth; on that day God

will be One and His Name will be One" (Zechriah, 14:9). Is He not One

today? Rabbi Acha bar Chanina said: "The World to Come is not like this

world. In this world upon hearing good tidings one says, 'Blessed are you etc.

Who is good and does good,' and upon hearing bad tidings one says, 'Blessed are

you etc. the True Judge.' But in the World to Come all the blessings will be,

'Who is good and does good.'"

"And His name will be One" -- is His name not One today?

Rabbi Nachman bar Yizchok said: "The World to Come is not like this world.

In this world God's Name is written with the letters Y/H/V/H, whereas it is

pronounced with the letters A/D/N/Y (spelling Adonay, meaning Lord or

Master), but in the World to Come it will be all one. It will be both

pronounced with the letters Y/H/V/H and written with the letters Y/H/V/H"

(Pesachim 50a).

The Kohen Gadol on Yom Kippur was referring to God by the

name He has in the next world, not by the name He goes by in this one. The

Satan has power in our world, and therefore God can only be described here as

A/D/N/Y, the Lord and Master, whereas in the next world, where the negative

force of the Satan does not exist, God is clearly the only Being.

Thus the first point about Yom Kippur is that it is a slice of

time that belongs to the next world rather than this one. By fulfilling the

commandments of the day Jews are elevated temporarily to the heady existence of

the World to Come where there is no Satan.

Thirteen Attributes of

Mercy

The next point concerns the 13 Attributes of Mercy. One of the

things we do on Yom Kippur in each of the prayers is recite the 13 Attributes

of Mercy several times. The recitation begins each time with a special emphasis

on the introductory phrase, which is repeated separately by the reader and the

congregation each time the 13 Attributes of Mercy are recited, as though it was

a significant phenomenon in and of itself, not merely an introduction to what

follows: "God passed before him and proclaimed..." (Exodus 34:6).

Rabbi Yochanan said: "If this wouldn't be expressly written

in the Torah, we would not even be allowed to think it. This teaches you that

God wrapped Himself in a prayer shawl like the leader of the congregation (who

is a messenger of the entire congregation) and showed Moses a method of prayer.

He told him, "Whenever Israel sins, they should pray in this manner in

front of Me, and I will forgive them" (Talmud, Rosh Hashana, 17b).

But what is so unthinkable about this? How does this differ from

other matters that God taught Moses?

Jewish tradition offers the following interpretation. The

difference between this world and the next is based on the manifestation of God

that is present in each. God created this world and manifests Himself in it

with His name Elohim. It is for this reason that the Divine Name Elohim

is interpreted to refer to the Attribute of Justice. This world is a place

where the Satan is also allowed to have power, where the fierce battle between

good and evil is constantly raging, and where there is judgment.

In the World to Come, God manifests Himself under the name YHVH.

In the World to Come, there is no evil, there is no battle with the Satan, and

therefore no judgment.

Although we refer to the world in which the name YHVH reigns

supreme as the World to Come, implying that it follows this one we live in now

and will only come into being at some future time, this is actually a misnomer.

This is true only from our point of view, for we must pass through the travail

and battle of this world in order to get to that one. But from God's point of

view that world comes first. It is closer to His Absolute Unity and in the

process of creation when God assumed His mantle of Creator, He was manifest

first as a single entity that is the sole source of all being, with no negative

anti-force in existence. From God's point of view, the World to Come already

exists.

Hidden Light

Because He wanted man to work for his reward, He hid part of the

brightness of the light shed by His Presence and made possible the existence of

an anti-force in order to provide an arena for man's exercise of free will.

From God's point of view, this sphere of revelation where the existence of an

anti-force is possible, represents a second, lower level of existence. This is

the separate world in which we live at present, where the holy name Elohim

is the proper designation for the revelation of God's presence that is

manifest.

As we have explained however, Yom Kippur is really a slice of time

cut out of the World to Come. In order to achieve this, the manifestation of

God in the next world must temporarily replace the manifestation of God in this

one. There must be a divine presence that sheds such an overpowering light that

the forces of the Satan are temporarily shut down.

On Yom Kippur ordinary reality is pushed out of the way. The

divine presence usually present in our world that gives shape to our ordinary

reality is intensified and brightened. Since the presence of the anti-force of

the Satan is inversely proportional to the brightness and intensity of God's

divine presence, as the light of God's presence intensifies, the presence of the

Satan is diminished. The voice of the anti-force is turned down. The only voice

that is heard throughout the world is the benign voice of the 13 Attributes of

Mercy.

We now have made two points. Yom Kippur corresponds to a level of

being that is really appropriate to the World to Come, and we access this level

of being through our prayers by reciting the 13 Attributes of Mercy.

Integration of the Soul

Let us attempt to bring these ideas down to earth a little more.

Jewish tradition teaches us that a person has five levels to his soul. The

three main ones are:

- Nefesh which is in his

body,

- the Neshama which is the

point where he is joined with God,

- in between, there is the Ruach

which unites the nefesh with the neshama.

The neshama, which is with God, is in the next world

already. The neshama is at the root of being, the nefesh at the

furthest extremity.

As long as all the parts of his soul constitute a single

integrity, no matter how porous such an integrity may be, a person stretches

all the way to the next world. He is a single entity at all levels. He belongs

in the World to Come in some fashion. What he needs to do is to straighten out

the contradictions and inconsistencies between the various levels of his soul

till they fit together in perfect harmony.

But what if he is a split personality, a spiritual schizophrenic?

His nefesh is so far away from expressing the personality

of his neshama, that for all intents and purposes there is no

correspondence between the two. As all the levels of the soul are fully alive

in themselves even when considered independently of each other, such a person

really breaks into two people. He is one person down here in this world, on the

level of his nefesh, and a totally different person at the level of the neshama,

which is with God in the World to Come.

Such being the case, he is treated by God as two separate people

who have nothing to do with each other. The nefesh being of this world

as it is in the body has one fate and the neshama another.

The commandments of Yom Kippur are two:

- To refrain from any sort of work as on

Shabbat, and

- To fast (the rabbis extended the

commandment to fast to include washing, wearing shoes and sexual

intercourse).

The commandments of Yom Kippur are designed to demonstrate that

our neshama and our nefesh are parts of a single integral unit

that is inseparable. Our nefesh behaves in the same way as our neshama.

It neither eats or drinks, or engages in intercourse or labor. It sits the

entire Yom Kippur in the synagogue, engaged in prayer and basking in God's

divine presence.

Integration of the soul is called teshuva, which means "to

return" in Hebrew. Through teshuva we return to ourselves. As long as we

are ourselves there is no need to return to God. We are already fully united

with His presence.

A day of atonement can be a day of judgment after all. Atonement

allows the various parts of the soul to integrate and return to each other once

again. When we succeed in this endeavor, the united soul is automatically

assured of being able to pass judgment. Atonement, spiritual purity and

judgment really do fit together very well.

http://www.aish.com/hhYomK/hhYomKDefault/judgment_tempered_with_mercy.asp

_______________________________________________________________

Yom Kippur article withhMessianic

content: :

Extracts from:

“WHY DO

I FAST AND PRAY ON YOM KIPPUR”

By Yitshak Kugler

A dear friend of mine declared

that since Yeshua had accomplished eternal atonement there was no need to fast

and pray on Yom Kippur in order to obtain atonement. To tell you the truth i

was rather flabbergast at his statement. First of all nobody in our

congregation thinks that by fasting and praying on Yom Kippur he gains atonement.

If we say that the Messiah has provided the atonement and obviated the need for

the Day of Atonement, then by the same logic we may say that Christ is our

passover sacrificed for us, so there is no need to celebrate Passover. My

friends response is a reflection of replacement theology in Christianity that

has persisted in one form or another since the days of the Church fathers. So

why do i as a Messianic Jew pray and fast on Yom Kippur?

Covenant Responsibility

First of all as a Messianic

Jew, i am a member of the covenant which God has made with the people of

Israel. God does not cancel covenants. In the Epistle to the Galations, Paul

declares that even with covenants of men no one comes with a subsequent

covenant to modify or cancel a former covenant, and certainly not with

covenants that are made by the faithful God. Perhaps the punishment clauses of

the Covenant that God made with Israel in Leviticus and Deuteronomy provide

first hand evidence that the Covenant is still in effect. The horrible persecutions,

exiles, and the holocaust provide ample evidence of the precision to which

these clauses are being executed. Even the return to Zion of our own days is

included in these clauses of the covenant. Over and over again in Scripture,

God declares through the prophets that even if Israel is sinful and unfaithful,

God will remain faithful to His covenants and accomplish His will and plan with

and through Israel. So if the covenant is still in effect, to ignore Yom Kippur

is to sin against the covenant. In times past when things were not so well

understood, we could understand that God would overlook our lapse, but in these

last days when a better understanding of Scripture is at hand, how can we

expect God to forgive a deliberate violation of one of the seven main appointed

times of His covenant. No, as a member of the covenant, the Day of Atonement is

given to me and our whole nation to keep.

Remembering the Atonement

Secondly, as a Messianic Jew, i

have been atoned for by the gracious atoning work of the Messiah. That in

itself is sufficient reason to observe the Day of Atonement. As a believer in

Yeshua, the fact is that i continue to sin - in spite of the fact that i have

been atoned for my sins. This sad and miserable fact is sufficient reason for

me to humble myself and afflict my soul in fasting and mourning at least one

day of the year and that at the appointed time given to our people by God. God

in His grace surrounds us with things and events to induce us to repentance and

holiness, and one of these is the Day of Atonement. If i pay attention to the

confessional that is recited at Kol Nidre, i have to confess that many of the

sins listed are ones of which i have been guilty, especially sins involving the

tongue and the lips. I feel that it is a gracious opportunity to confess and

apologize before the Lord my failure, determine in my heart to do all that i

can to avoid repeating these mistakes again and pray the Lord’s help by His

spirit to enable me to overcome. As to the idea that by fasting and praying on

the Day of Atonement i can obtain atonement, it is absurd. The Day of Atonement

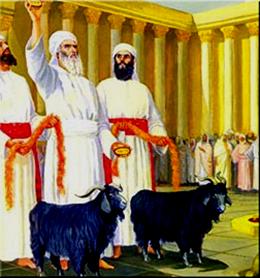

never provided atonement to the individual Israelite. Nor was it ever possible

that the blood of bulls and goats to take away sin. Rather we have been sanctified

through the offering of the body of the Messiah Yeshua once for all time.

Notwithstanding this every believer in Yeshua will give an answer to Him at the

Judgement seat of the Messiah for every un-confessed sin. The day of Atonement

provides me with one more opportunity to confess my sin before the Lord and

receive His forgiveness by virtue of the atoning work of the Messiah. Of course

I can do that at any time, but certainly i should do it on the Day of

Atonement.

Mindful of those who do

not have the Atonement

Thirdly, I feel that on the day

of Atonement of all days of the year, it is the opportunity to fast and pray

before the Lord on behalf of those who are lost and perishing all about me. Of

course i can and do pray that way many times. There is no better day of the

year given to our people by God for fasting and praying for the atonement of

our people and individual Jewish people than the Day of Atonement.

The Testimony of the Day

of Atonement

The Day of Atonement and the

Ten days of Awe preceding provide a powerful contextual statement of the

reality of sin in the life of our people and our nation. No other nation or

religious community dedicates 10 days of the year to think about sin, yet in

Israel it is a deeply established element of our culture. In the world today

and no less among the people of Israel today there is a wide spread and deeply

engrained denial of sin. This psychological defense mechanism is even more

deeply rooted because people do not have a sure way of expiation (atonement) for

their sin. I as a Messianic Jew can point out that on Yom Kippur we all say “We

have sinned, we have transgressed, we have committed iniquity…” and that God

has not left Israel bereft and without His appointed means of Atonement, the

Messiah’s offering up of His own eternal soul to atone for the sins of our

people.

Prophetic Significance of

the Day of Atonement

The Day of Atonement speaks of

that day in the future when all Israel will be saved. As it is written:

And I will pour out on the

house of David and on the inhabitants of Jerusalem the Spirit of grace and

supplication, so they will look to me whom they have pierced … On that day

their will be great morning in Jerusalem.

The seven appointed times

listed in Leviticus 23 are a symbolic and prophetic outline of the work of

God’s salvation in the Nation of Israel, and for the whole world. Of all these

appointed times, the long awaited great day of national salvation in which all

of Israel who survive to that day will be saved - on the Day of Atonement.

Biblical Understanding of

the Place of the Day of Atonement

The classical hermeneutical

framework of the Christian Church has been that Christ has inaugurated the New

Covenant which supercedes the Old Covenant and that the Church replaces the

people of Israel as the people of God. This hermeneutical framework of

supersessionism has consistently lead believers in Yeshua to regard the

Covenant that God has made with the people of Israel as being obsolete and

void. During this century, Jewish believers have been slowly finding their way

back into an understanding of their covenant relationship with God and with the

people of Israel. The New Covenant does not replace the covenant of God, rather

it enables its members to abide by God’s Torah by virtue of God’s Torah being

written on the tables of our heart, it provides for a saving knowledge of the

LORD, and it provides forgiveness of sin for the believer.

http://www.netivyah.org.il/

______________________________________________________________

PREPARATIONS

FOR SUKKOT:

By Breslev Israel staff

You

shall dwell in booths for a seven-day period…So that your generations will know

that I caused the Children of Israel to dwell in booths when I took them from

the land of Egypt.”

The Holiday of Sukkot

One

of the three pilgrimage festivals that the Jewish people were commanded to

celebrate each year is Sukkos – the Festival of Booths, which lasts a week from

the 15th to the 21st of Tishrei (and in the Diaspora

until the 22nd). The first day is a Yom Tov, and the rest of the 7

days are known as the Intermediate Days of the Festival. (A separate Festival

–Shemini Atzeres or Simchas Torah – immediately follows Sukkos on the 8th

day, the 22nd of Tishrei in Israel and on the 23rd in the

Diaspora).

The source in the

Torah is in Vayikra (23:34-35,41): “On the fifteenth day of this seventh month

is the Festival of Booths, a seven day period for Hashem. On the first day is a

holy convocation; you shall not do any laborious work…You shall celebrate it as

a festival for Hashem, a seven-day period in the year, and eternal decree for

your generations; in the seventh month shall you celebrate it.”

The source in the

Torah is in Vayikra (23:34-35,41): “On the fifteenth day of this seventh month

is the Festival of Booths, a seven day period for Hashem. On the first day is a

holy convocation; you shall not do any laborious work…You shall celebrate it as

a festival for Hashem, a seven-day period in the year, and eternal decree for

your generations; in the seventh month shall you celebrate it.”

Dwelling

in the Sukkah (booth) is an integral part of the Festival. During the week we spend

more time in the Sukkah than in our house. It is an uplifting spiritual

experience to live in the Sukkah, and a quality family time as well.

The

Sefer Chinuch (the Book of Education, which explains the 613 Mitzvot

(Commandments) according to their Biblical source) writes concerning the

Mitzvah of dwelling in the Sukkah: “One of the roots of the Mitzvah is explicit

in the Torah: In order that we should remember the great miracles that G-d made

for our forefathers in the desert during the Exodus from Egypt. He surrounded

them with the Clouds of Glory so the sun wouldn’t harm them in the day and the

frost at night. Some explain that we commemorate the actual booths that the

Children of Israel made in the desert.”

Even

though the Exodus was in the month of Nissan, we weren’t commanded to make the

Sukkos in Nissan, because in the balmy days of Nissan farmers  are

accustomed to leave their homes and enjoy themselves in the shade of booths

outdoors. It wouldn’t be so obvious that we are making the Sukkah as a Mitzva

of Hashem. During Tishrei, however, when the nights are cold and the rainy

season is about to begin, farmers return to their homes. When we do the

opposite, leaving our homes and dwelling in a Sukkah, we are demonstrating that

the purpose of the Sukkah is the Mitzvah of Hashem.

are

accustomed to leave their homes and enjoy themselves in the shade of booths

outdoors. It wouldn’t be so obvious that we are making the Sukkah as a Mitzva

of Hashem. During Tishrei, however, when the nights are cold and the rainy

season is about to begin, farmers return to their homes. When we do the

opposite, leaving our homes and dwelling in a Sukkah, we are demonstrating that

the purpose of the Sukkah is the Mitzvah of Hashem.

Sukkos

falls in the harvest season, a time of plenty, when the farmer brings his

produce into his silo. A man naturally feels haughty when he is wealthy, and

thinks: “My strength and the might of my hand have made this wealth.” To

counteract our tendency to arrogance the Torah commands us to leave our houses

filled with the abundance of wealth in the harvest-time and to dwell in a

Sukkah. All a man needs for happiness is G-d’s protection symbolized by the sechach

(the leafy covering over his head in the Sukkah); even in the flimsy,

temporary booth he can be full of joy in appreciation of what G-d has given

him.

The

Midrash says: “Why do we build the Sukkah after Yom Kippur? Because on Rosh

Hashana G-d judges the entire world, and on Yom Kippur the judgment is sealed.

Perhaps the Jewish people are obligated to go into exile? Therefore they make a

Sukkah and exile themselves from their homes to the Sukkah.”

Living in the Sukkah

The

Sukkah should be made as beautifully as possible. Our Sages said: “Glorify Him

with the Mitzvot. Make a beautiful Sukkah, beautiful Lulav, etc. As it says:

‘This is my G-d and I will glorify Him…’” It’s a Mitzvah for a person to attend

to building the Sukkah himself.

The

Torah instructs us to live in the Sukkah the way one would live in his home.

The Sukkah becomes his place of residence for the seven days of Sukkos. He

should eat all his meals and entertain guests there. One should sleep in the

Sukkah even if he only needs to nap.

Building the Sukkah

The

walls of the Sukkah can be built from any material: wood, plastic, metal or

stone; it must be sturdy enough to stand in an ordinary wind.

The

dimensions of a Sukkah:

A

Sukkah has at least three walls. The walls may not be elevated off the ground

more than 3 tephachim (24 cm.) so that a small animal can’t crawl

inside. The height must be more than 10 tephachim (80 cm.) but less than

20 ama (9.60 meters). The width of the walls must be at least seven tephachim

(56 cm.).

After

setting up the walls one places the sechach (the leafy covering that

provides shade) as the roof, using thin, narrow boards, placed horizontally on

top of the walls to support it. Many people use tree branches, palm fronds or

bamboo; specially prepared bamboo mats are available. The principal explained

in the Oral Law is that the sechach must be something which 1) grew in

the earth, 2) was completely uprooted or detached from the plant, and 3) was

never made into an instrument or vessel (such a table or barrel). One may not

use a foul-smelling thing for sechach, nor branches whose leaves fall

off during Sukkos, because these types of sechach may cause him to leave

the Sukkah.

A

Sukkah may not be built under tree branches that make shade over the Sukkah.

The amount of sechach should be enough that the shade provided by the sechach

in the Sukkah is more than the sunlight that passes through, but not so much

that no stars can be seen at night through the sechach, or that rain

could not penetrate.

The Four Species

The

Torah states (Vayikra 23): “You shall take for yourselves on the first day the

fruit of a citron tree, the branches of date palms, twigs of a plaited tree,

and brook willows; and you shall rejoice before Hashem your G-d seven days.”

The

Sefer Chinuch (the Book of Education) says:

“One of the

roots of this Mitzvah is that a man is affected by the actions that he does

continuously, his ideas and feelings follow his actions. Because G-d wanted to

bring merit to His Chosen People, He gave them many Mitzvot so they would be

affected beneficially by performing them daily.

“One of the

roots of this Mitzvah is that a man is affected by the actions that he does

continuously, his ideas and feelings follow his actions. Because G-d wanted to

bring merit to His Chosen People, He gave them many Mitzvot so they would be

affected beneficially by performing them daily.

“The

Festival is a time of joy for the Jewish people, since it’s the harvest season,

when they bring the fruits of their labor into the home and people are

naturally happy. G-d commanded them to make a Festival at that time, so they

will have the merit that their joy and happiness can be dedicated to His Name.

Joy may cause a person to be drawn after materialism and forget his fear of

Heaven, so the Creator commanded His people to take items in their hands to

remind them that all their joy should be dedicated to His Name and His honor.

He wanted these reminders to be items that bring joy, just like the time of

year, and it is well known that the four species are naturally endowed to bring

joy to the heart of man when he gazes upon them.

“Furthermore,

the four species resemble precious organs of a human being:

The

Esrog

(citron) – resembles the heart (meaning the mind), which is the place of

our intellect, to teach us that one must serve G-d with his intellect.

The

Lulav

(palm

branch) – resembles the spine, the main part of a human being, to teach

us that a man must focus his entire body to serve G-d.

The

leaf of the Hadas (twig of a plaited tree, the myrtle) – is the shape of

an eye, to teach us that our eyes should not lead us astray on the day

of our joyous Festival.

The

leaf of the Arava (brook willow) – is in the shape of the lips,

which hint at speech, to teach us that a man should rein in his speech and be

careful with what he says even in the time of joy.”

The

Mitzvah of the four species teaches us that we must seek to bring all the

Jewish people closer to their Father in Heaven, no matter how distant they may

be. We find in the Midrash that each one of the four species symbolizes a

different type of Jew:

“The

fruit of a beautiful tree – The esrog has both taste and scent –

these are the Jews who possess both Torah learning and good deeds.

The

branch of the palm tree – The lulav has taste [i.e. the dates] but lacks

scent – these are the Jews who posses Torah learning but lack good deeds.

A

twig from the plaited tree – The hadas has scent but lacks taste –

these are the Jews who have good deeds but lack Torah learning.

Willows

of the brook –

The arava lacks both taste and scent – these are the Jews who lack both

Torah learning and good deeds.

What

does G-d do with them? To destroy them is unthinkable. Rather G-d says, ‘Bind

them together in one bond and they will atone for each other.’”

The

Midrash teaches us that even those that have no taste or scent – neither Torah

nor good deeds – must not be distanced; rather we are to bind them together

with the species that have a scent so they will absorb the good scent. In this

way we must reach out to our estranged brothers and bring them close to the

Torah scholars, who have both “taste and scent,” and the scholars will have

good influence upon them until they come to resemble the Esrog themselves,

possessing Torah and good deeds.

The

Mitzvah of the four species can only be fulfilled if all the four are held

together simultaneously. The Jewish people are the same, even though we are so

different from one another, we must always be unified.

“You Shall Rejoice on

Your Festival”

On

all Holidays we are commanded, “You shall rejoice on your Holiday,” but on

Sukkos the joy is doubled and tripled, “And you shall be only joyous.” In our

prayers we call the Festival of Sukkos “the time of our rejoicing.” We are

enjoined to show our rejoicing by eating meat and drinking wine, wearing fine

clothing, dancing, singing and laughter.

On

the other Festivals we rejoice because of a specific historical event, such as

the Exodus on Pesach or the Giving of the Torah on Shavuos. But on Sukkos,

Simcha (joy) is the essence of the Festival. Therefore the Mitzvah to rejoice

on Sukkos is very great. We must rejoice in truth, with all our heart. We

rejoice that we have G-d, we’re happy for the connection we have with Him with

all our being. We’re happy He cares for us like a father cares for his beloved

child.

The Ushpizim – The

Exalted Guests

The

Zohar HaKadosh writes: “When the People of Israel leave their homes and

enter the Sukkah for the sake of G-d’s Name, they merit to welcome the Divine

Presence there, and all the seven shepherds descend from Gan Eden and come to

the Sukkah as their guests.” The seven shepherds include the Patriarchs of the

Jewish people who wandered from exile to exile and attained rest only after

great toil and travail.

It

is customary, upon entering the Sukkah, to invite the ushpizim to enter

by reciting the traditional Aramaic formula contained in the prayer book:

On the first day –

Avraham Avinu (the Patriarch)

On the second day – Yitzchak

Avinu

On the third day –

Yaakov Avinu

On the fourth day –

Yosef HaTzaddik (the Righteous)

On the fifth day –

Moshe Rabbeinu (our Teacher)

On the sixth day –

Aharon HaKohen (the High Priest)

On the seventh day –

David HaMelech (The King)

Among

the Sephardim, it is customary to prepare an ornate chair in the Sukkah, which

is covered with a fine cloth and upon which holy books are placed. The host

declares: “This is the chair of the ushpizim.”

Since

the Sukkah of the Festival is a dwelling for the Divine Presence and the

exalted guests, it is proper that one also invite guests of flesh and blood,

i.e., poor people, to share one’s meals in the Sukkah, to please his Heavenly

guests.

The

Sukkah is the dwelling place of the Divine Presence, so one must be careful not

to speak meaningless conversation in the Sukkah, certainly, even more so, he

must avoid slander and gossip. Rather one should focus on words of Torah. One

should behave in a very honorable way in the Sukkah so as not to drive away the

Divine Presence.

The Names of the

Festival

The

Festival has a number of names:

The

Harvest Festival

– This was the time when the farmers brought their produce in from the fields.

The

Time of our Rejoicing

– The Torah emphasized rejoicing on Sukkos.

Shemini

Atzeres

and Simchas Torah

- The

eighth day of the Festival (and the ninth in the Diaspora) is a special Day of

Assembly.

The Pilgrimage

Sukkos

is one of the three Festivals in which the Torah commands the People of Israel

to go up to Jerusalem, to the Holy Temple, and to offer special sacrifices. The

three Festivals are Peasch, Shavuos and Sukkos. Today many are accustomed to

visit the Western Wall in Jerusalem to commemorate this Mitzvah.

The

three Pilgrimage Festivals are connected to working the land:

Pesach – They would bring

the Offering of the Omer, from the first ripening barley.

Shavuos – The first ripening

of the wheat harvest was offered.

Sukkos – The time of

harvest.

Hoshana Raba

The

Hoshana prayers are recited in the Synagogue each day of Sukkos as we

circle the bima holding the lulav and esrog. These prayers

are for redemption, and are referred to as Hoshanos because each stanza

of the prayer is accompanied by the word hoshana – a combination form of

the words hosha and na – bring us salvation, please. The seventh

day of Sukkos is called Hoshana Raba – literally, the great Hoshana,

because on this day more Hoshana prayers are recited than any other day

in Sukkos.

Hoshana

Raba

marks the day when the judgment, which begins on Rosh Hashana, is sealed. At

the beginning of the period, on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, the entire world

passes before G-d in individual judgment. On Sukkos, the world is judged

concerning water, fruit and produce. The seventh day of the Festival, Hoshana

Raba, is the day that this judgment is sealed. Because human life depends

on water and all depends on the final decision, Hoshana Raba is invested

with similarity to Yom Kippur and is marked by intense prayer and repentance.

We

find in a Midrash:

G-d

said to Avraham: “I am one and you are one. I will grant your descendants one

single day on which they can atone for their sins – Hoshana Raba.

The

Mateh Moshe explains that G-d told Avraham that should Rosh Hashana be

insufficient to atone for their sins, then Yom Kippur will atone. And if Yom

Kippur does not, then Hoshana Raba will.

Why

was this promise made specifically to Avraham? Avraham’s light began to

illuminate the world after twenty-one generations [counting from Adam].

Similarly, even if Israel’s light is late in shining, it will not be delayed

for more than twenty-one days after Rosh Hashana – i.e., on Hoshana Raba.

The

custom is to remain awake all night on Hoshana Raba and to read from a special Tikkun.

The essential character of the day is prayer and the awakening of Divine mercy

at the time of the sealing of judgment and the issuing of “notes of decision” –

the verdicts. This is the source of the custom of wishing one another a pitka

tava – Aramaic for a “good note.”

http://www.breslev.co.il/articles/holidays_and_fast_days/sukkot_and_simchat_torah/the_guide_for_sukkot.aspx?id=1107&language=english

SHALOM UVRACHOT

PEACE AND

BLESSINGS

Editors:

Compiling

editor: Agatha van der Merwe

Content

control: OvadYah Avrahami

Participating

editors: Dr Robert Mock, Geoffrey Meservy-Norman, Stephen

Spykerman

Torah

Guidance: Rabbi Avraham Feld

Disclaimer:

The editors

and especially Rabbi Feld, do NOT necessarily agree with all the contents

and/or statements of articles used in this Newsletter, neither with views

expressed by these authors in their personal writings or promotions. This is

presented as a service only, for gleaning information, to guide Returning and

re-identifying 10-Tribers towards Reconciliation. The basic guidelines of

agreement for Reconciliation as recommended by the Kol HaTor Vision, are

contained in the “Uniting Factors” as published on its official Web Site at http://www.kolhator.org.il

Subscription –

Regular subscription to this News letter is for Active

Participating Associates of the KOL HA’TOR VISION only – who may freely forward

and distribute it as they wish.

To register

for KHT association, please complete your registration details at http://www.kolhator.org.il/join_us.php

Return to the Home Page | Translate this Page

Return to the Home Page | Translate this Page